The late legendary musician Charles Neville is the inspiration for Blues to Green, founded and directed by his wife, Kristin Neville. To share his legacy with the world, she partnered with The Springfield Museums to create and display an exhibit about his life.

Come learn about Charles’ youth growing up in New Orleans amidst poverty, Mardi Gras music, and Voodoo, then touring the segregated South with a Black vaudeville show. Listen to the musical influences in his life and follow the story of his prison experience as a target of the racist War on Drugs, his rise to fame touring the world with The Neville Brothers, his decades-long struggle with addiction and eventual victory, and his life with his wife and sons in western Massachusetts, where his wife founded Blues to Green and the Springfield Jazz & Roots Festival to spread his legacy of using music to overcome racial injustice and bring people together in joy.

Click here to visit the Wood Museum exhibit website.

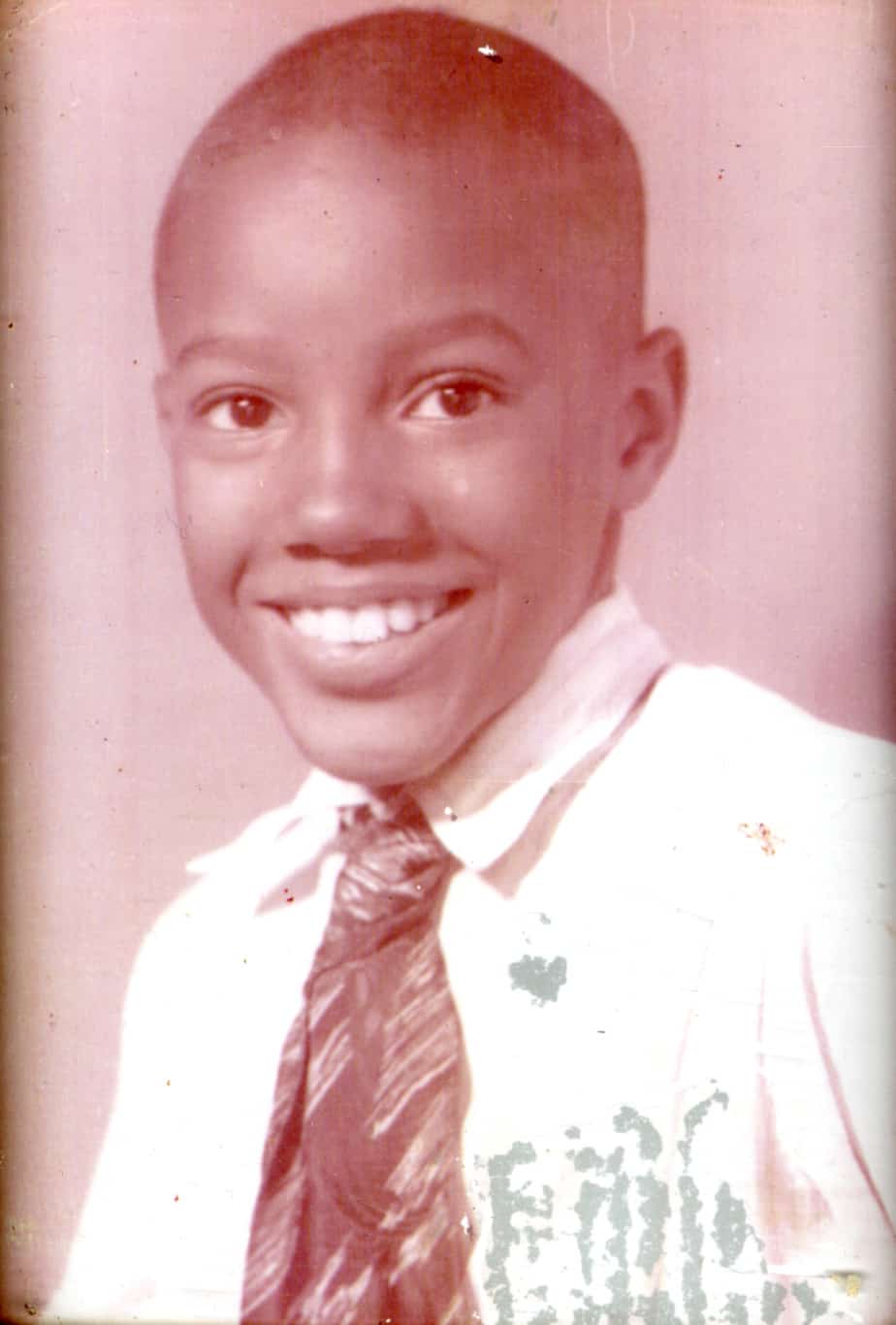

Charles was born on December 28, 1938 into a musical New Orleans family, nephew of the Mardi Gras Indian Big Chief Jolly. His home had no plumbing or electricity, only an outhouse, but there was always music; everyone sang or played an instrument. Moving into the projects was a step up to bathrooms, electricity, and well-kept yards with kitchen gardens and chickens. Second of six siblings, he grew up without a TV; everyone played music together instead, and when he saw Louis Jordan playing saxophone in a short at the Black movie theater, he knew that would be his instrument.

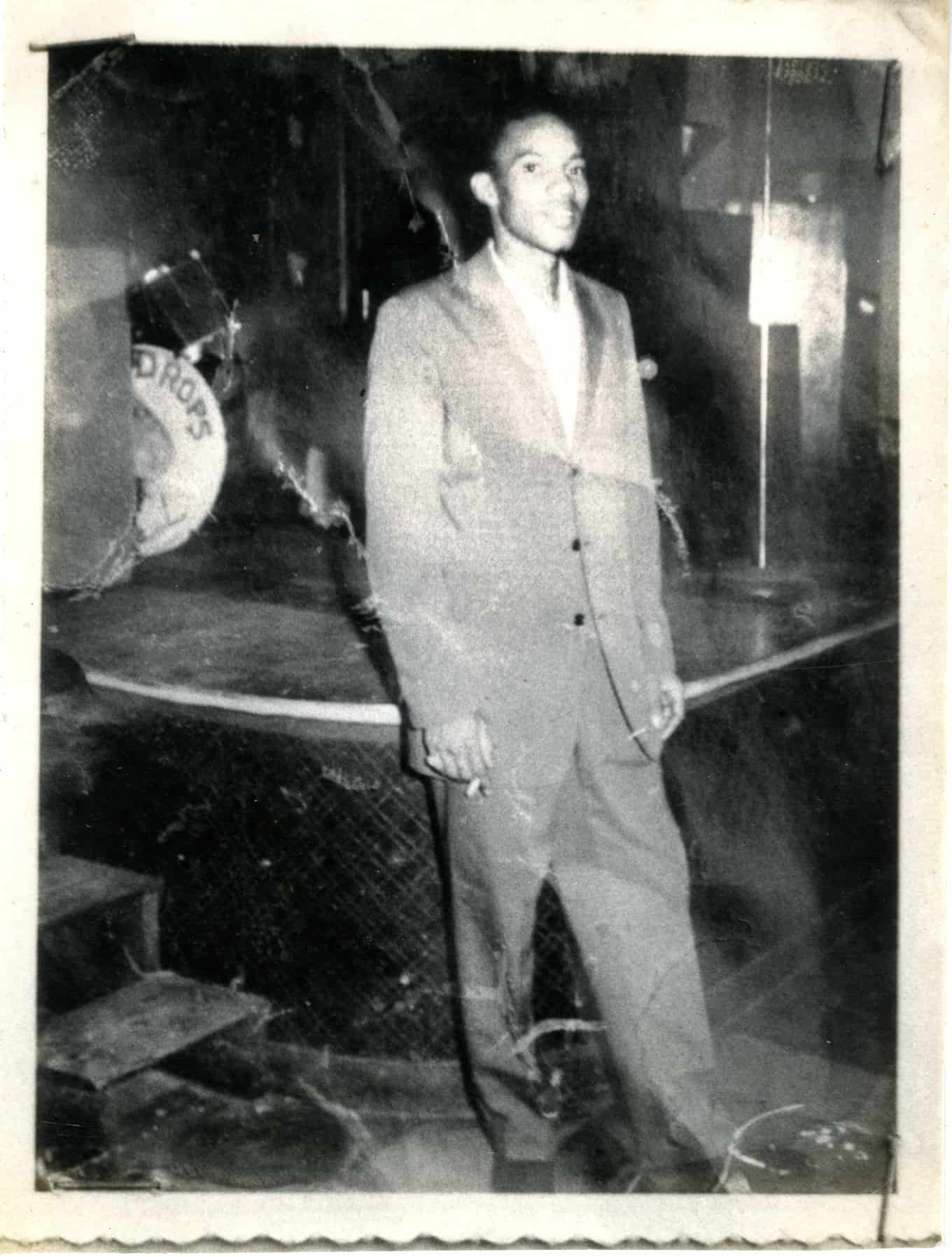

Charles grew up voraciously reading everything from westerns to sci-fi to Shakespeare to philosophy, and he played sax with New Orleans greats like Fats Domino, Kris Kenner, Allen Toussaint, and James Booker. At 15 he dropped out of school to tour the South with The Rabbit’s Foot Minstrel show, and Gene Franklin and His Houserockers.

Touring the South with Gene Franklin and other bands, the adventurous young Charles played sax with BB King, Big Joe Turner, Larry Williams, Big Maybelle, Jimmy Reed, Little Walter, Johnny Ace, and many others. He also backed outlandish acts like Iron Jaw, who swallowed coke bottles and tap danced while balancing a table up between his teeth – with a woman sitting in a chair balanced on it.

In 1956, at 17, he joined the Navy to see the world … but was stationed only in Memphis, where he played sax and hung out with stars like BB King and Elvis Presley. After getting out of the Navy in 1958, he toured with BB King and Larry Williams.

Hooked on heroin as a teen, Charles was sometimes driven to shoplift to fund his addiction. He served short jail terms, and in 1963, at 24, was sentenced to five years of hard labor for possession of just two marijuana joints. In the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, beatings, rape, solitary confinement in the infamous “dungeon,” and starvation diets were commonplace. Fortunately, Charles was put to work teaching music and spent his term honing his craft alone and with other talented imprisoned musicians like James Booker and James Black. Music and books were his refuge from the dehumanizing and often racist violence. “Angola Bound” a song he co-wrote with his brother Aaron, commemorates this time and honors friends incarcerated at Angola and young men being sent there with no idea how horrible it is.

After prison, Charles got hooked on methadone, used to help people get off of heroin, but he found its withdrawal symptoms even worse. For decades, every time he tried to quit, he got so sick for months on end that he wound up shooting heroin for relief and starting the cycle all over again.

After release, Charles moved to New York City, dove into modern jazz, and toured with soul singers like Johnnie Taylor, Clarence Carter, and OV Wright. He had no interest in fame or even recording; music for him was about being in the moment, playing for the audience right there. Despite – or because of – all he’d been through, people always found his energy grounded, centered, peaceful, and tender. An extremely sensitive and versatile artist, his music was spiritually and emotionally intense, a universal language and unifying force, and his relationship to it was spiritual. “The sound of the tenor [sax] is feminine and masculine,” he said, “and there’s a spirit in it that is expressed in the sound, so it’s the person playing it’s spirit and the spirit of the horn combining to make whatever comes out of it.”

In 1976, when Charles was 37, his uncle George Landry, the Mardi Gras Indian tribe leader Big Chief Jolly, drew him and his brothers back to New Orleans to record “The Wild Tchoupitoulas” album, bringing their Mardi Gras Indian Tribe into the studio to play with them. Fusing traditional street chants with funk, the album instantly became a cornerstone of modern New Orleans music.

Like Charles, his brothers were already accomplished musicians in their own right: Art had sung the 1954 hit “Mardi Gras Mambo” and in 1969 formed the influential New Orleans funk band The Meters, which Cyril later joined, and Aaron’s “Tell It Like It Is” was a 1966 Top 10 pop hit. Big Chief Jolly convinced the four talented brothers to keep making music together, and The Neville Brothers band was born.

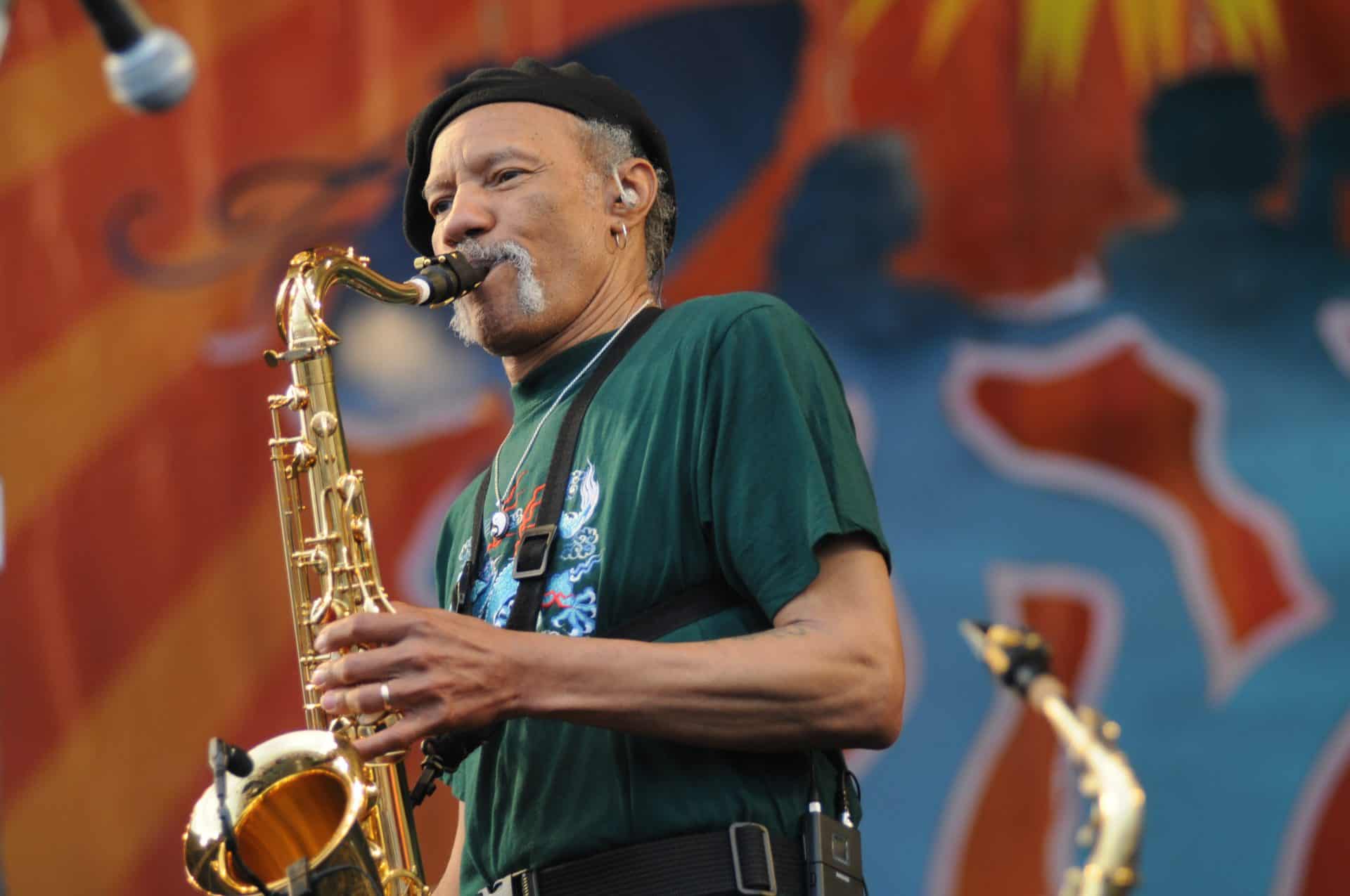

Combining doo-wop, soul, funk, Latin, R&B, gospel, jazz, blues, bebop, and New Orleans Mardi Gras rhythms, The Neville Brothers’ music, derived from African and African American roots, was great for parties and always socially conscious. They gained a national and worldwide following on tour and might have become a household name if their music were not so difficult to classify and fit to specific radio stations. Affectionately known as “The Horn Man” by his brothers, Charles usually performed in a beret and tie-dyed shirt, with irrepressible joy at the beauty of the moment.

The brothers were the prestigious perennial main stage finale of the huge annual New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, played major New Year’s Eve shows at the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco, and recorded over a dozen studio and live albums. The most popular, “Yellow Moon” (1989) sold over a half-million copies; one of its songs, “Healing Chant,” centered a sublimely soulful sax solo by Charles, won a Grammy Award for best pop instrumental.

Charles’ addiction lasted nearly 30 years; he had to stop at methadone clinics wherever he played. Finally in 1986, at 47, he went to Serenity Lane in Eugene Oregon, where everyone, even the doctors, was in recovery together. After a 60-day live-in program and a yearlong daily outpatient program, Charles was finally liberated from addiction and remained so for the rest of his life.

All four brothers continued with their own separate projects while playing together. Charles had another band, Diversity, which mixed jazz and orchestral musicians, and he played with the American Indian band Songcatchers. With The Neville Brothers and independently, he toured and performed with The Rolling Stones, The Grateful Dead, Carlos Santana, Tina Turner, John Hammond, Billy Higgins, Tiny Grimes, George Coleman, Jack Bruce, Steve Swallow, Robby Amin, Horacio “El Negro” Hernandez, Giovanni Hidalgo, Herbie Hancock, Archie Shepp, Avery Sharpe, Dr. John, Lou Soloff, John Stubblefield, Bonnie Raitt, Carmen Lundy, Michael Doucet, and many more.

Through it all, Charles remained humble and down-to-earth. One of his greatest gifts was how he always reminded those around him to live in the beauty of the moment and share it with one another. When a journalist expressed this to him in an interview, he said that may be part of his purpose for being here. Quoting the Dalai Llama, he added, “Lovingkindness is my religion.”

In the 1990s, after marrying Kristin Gaitenby (now Kristin Neville), Charles moved to rural Western Massachusetts, where they built a strawbale house and yurt on the dirt road where she grew up. Charles continued to tour while Kristin stayed home raising their two sons, Khalif and Talyn.

In 2012, after an incredible 35 years together, the Neville brothers wanted a change and went their separate ways artistically. Charles was 73. He then performed with his sons as The New England Nevilles, and with his brother Aaron’s band, and his daughter, singer Charmaine Neville (he had several children before meeting Kristin). He returned also often to play in New Orleans. After Kristin launched Blues to Green in 2013 and the Springfield Jazz & Roots Festival in 2014, Charles supported her work, performed on stage and gave music workshops for children annually, and spoke in the festival’s public Jazz & Justice discussion.

With a musical career spanning 60 years playing with world-class musicians in multiple genres, Charles was part of the evolution of jazz, blues, R&B, and rock from their roots in the musical cultures of New Orleans and the Mississippi River Delta. Faced with racism, addiction, criminalization, and violence, Charles used music to keep his spirit centered, gentle, and kind. He exemplified courageous, peaceful resistance, using music to touch diverse people and unite them in common humanity across racial divides.

It is no wonder that Charles’ life, music, and spirit inspired his wife, Kristin Neville, to found Blues to Green in 2013 as a nonprofit using music of the African diaspora to bring people together, build shared purpose, and catalyze social and environmental change.

Charles was a great support for Kristin’s hard work for Blues to Green until pancreatic cancer led to his passing in 2018 at the age of 79. To honor and share his legacy, the Springfield Jazz & Roots Festival main stage has been named after him, and the Charles Neville Legacy Project will bring acclaimed musicians of color into Springfield public schools, using music to teach history and literature while centering Black people and social justice. Kristin is also working with The Springfield Museums on a Black history exhibit spotlighting Charles’ life in summer 2021. He will always live on through his music, his family, and Blues to Green.